Yanbaru—Getting Back to Nature

Explore the forests, mangroves, waterfalls, and unique wildlife of Yambaru National Park.『Paddle through mangroves and take a guided night walk to spot rare fauna.』

Lush green forests, mangroves, waterfalls, and unique wildlife make Yanbaru the perfect place to immerse yourself in an idyllic landscape, and unwind from the hustle of everyday life and reconnect with mother nature. In 2016, Yambaru National Park was established in the north of the main island of Okinawa. Its pristine subtropical forests and indigenous animals and plants have led to its nomination as a combined UNESCO World Heritage Site, alongside Iriomote Island (Okinawa) and Amami-Oshima Island (Kagoshima).

For visitors, Yanbaru is easily accessible by car from the southern part of Okinawa’s main island, so take this chance to discover its natural beauty. As a photographer, I love the opportunity to document the local culture, flora, and fauna. With this in mind, I packed my camera bag and drove north for a weekend adventure in Yanbaru.

DAY 1: Mangrove kayaking and night hiking

Driving up the west coast, I passed through Nago City, the northern bastion of urban life in Okinawa. From here on, the traffic becomes scarcer, and the pace of life slows. I stop by Kunigami Minato Shokudo, aka “fisherman’s diner,” to catch up with the owners, Hiromi and her son Hitoshi. Hitoshi prepares sashimi dishes for eager customers, carefully slicing tuna, octopus, yellowtail, snapper, and other locally caught fish.

This family restaurant is just meters from the ocean, which provides both the ingredients for the dishes and a calming backdrop. Okinawans often describe themselves as uminchu, or “ocean people.” For Hiromi, she says that she can’t imagine living or working where she couldn’t be right next to the beautiful Okinawan ocean.

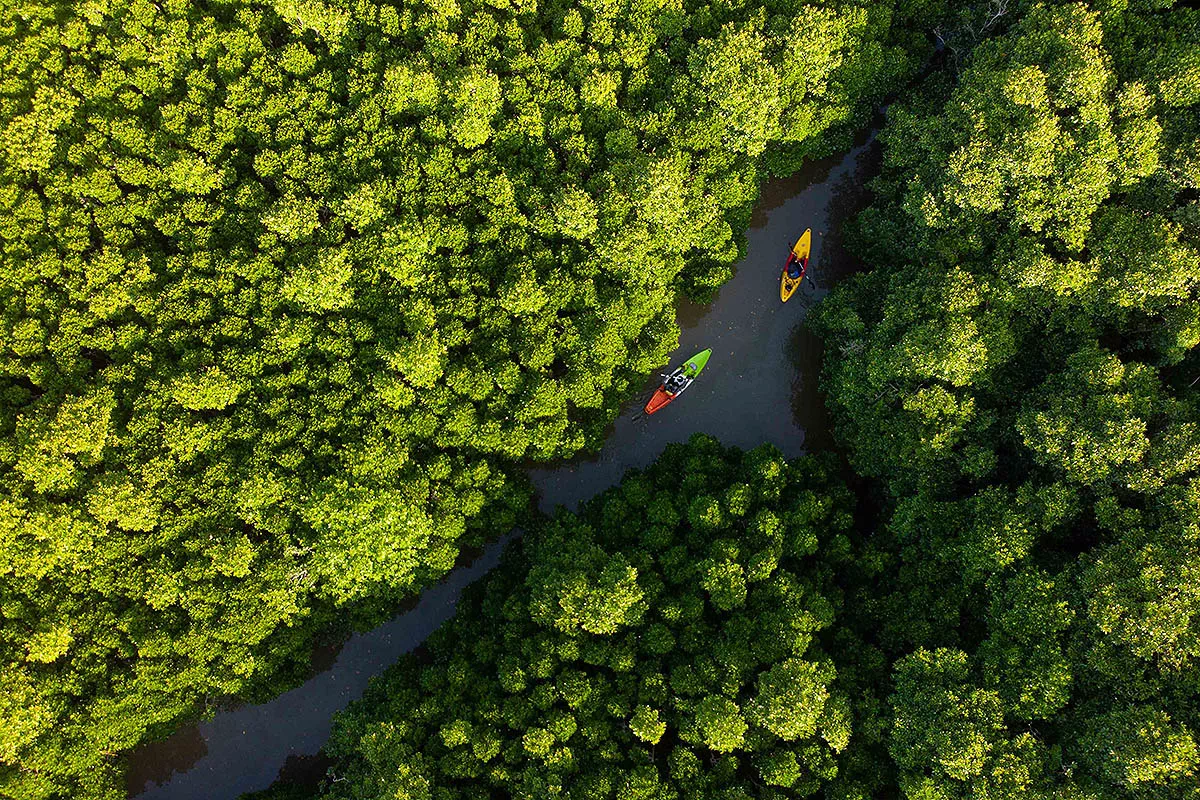

Next, I drove east to the mangroves around Hirugi Park. This particular ecosystem of plants and animals thrives in the mix of freshwater from the river and the tidal flows of seawater from the ocean. Visitors can explore the mangroves via a network of elevated walkways, but a more adventurous and informative option is to join a guided kayak tour. It had been a few years since I’d been on a kayak, but my guide Ms. Enishi reminded me of the basics, and the calm river meant I didn’t need whitewater skills.

As we gently paddled up the Kesaji River and through the mangroves, Ms. Enishi pointed out the mudskippers lounging on the riverbanks and the various salt-tolerant plants that thrive here. Originally from Osaka, Ms. Enishi moved to northern Okinawa, and loves being close to nature. “There are no supermarkets or big stores here, but I love living and spending time in Yanbaru.”

Late in the afternoon, I headed a little further up the coast to meet up with my nature guide Mr. Oda. Although most of Yanbaru’s animals are active during the day, many only appear once the sun has set. Mr. Oda handed me a flashlight, and together we explored along the edge of the woodland. Away from streetlights, roads, and buildings, my initial impression was of silence and darkness.

Slowly my senses adapted, and I heard the hoot of an owl from a distant tree, the rustle of leaves as a lizard scuttled away, and frogs’ croaking. As we moved in the direction of the frogs, Mr. Oda explained that we’re not the only ones that are out searching for creatures. Habu, Okinawa’s venomous pit vipers, are nocturnal, and frogs are their favorite meal. We both scanned the edge of a small pond where we could hear the frogs, and sure enough, there was a hime habu, aka the princess viper, curled up at the water’s edge. Her highness had no interest in us, and I had no desire to get any closer, so we explored deeper into the forest.

In the moonlight, I saw fruit bats flitting above us, while another species of owl began to call. Once again, Mr. Oda checked the undergrowth with his flashlight until he spotted something, and beckoned me over. Sitting among the leaves was a species of gecko I’d never had the chance to see before. The only place in the world where you can find the Kuroiwa’s ground gecko (Goniurosaurus kuroiwae) is in Okinawa’s forests. Mr. Oda held the flashlight so that I could take a few photos. In the darkness, he couldn’t see the grin on my face, but I was delighted to have encountered one of Yanbaru’s iconic residents. Mr. Oda is trying to protect species threatened by poachers with this night patrol.

There are camping areas in Yanbaru, but that night I stayed at the Ada Garden Hotel, not far from the tiny village of Ada. The hotel embraces its location in this wildlife haven, with photographs of the local flora and fauna decorating the walls of the lobby and stairs. The staff was friendly and even able to accommodate my request for vegan meals.

DAY 2: Bird watching and nature trail

The Kuroiwa’s ground gecko isn’t the only creature that is unique to Okinawa. Bird watchers from around the world visit Yanbaru to add rare species to their life list. Yanbaru kuina (Okinawa rail), noguchi gera (the Okinawa woodpecker), and the Ryukyu robin are all endemic to the forests of Yanbaru, and there are Okinawan subspecies of birds such as the varied tit, Japanese white-eye, narcissus flycatcher, and the ruddy kingfisher. The only essentials for a budding ornithologist are a pair of binoculars and a field guide. Still, your best chance of spotting and identifying the various species is to meet up with a local birder. Luckily, I know just the man, wildlife artist, and naturalist, Ichiro Kikuta.

Mr. Kikuta and I took a short drive to a viewpoint in Ibu where we could see the sunrise over the ocean. As the dawn chorus began, Mr. Kikuta identified each bird we heard; a blue rock thrush, Japanese bush warblers, a flycatcher, and wagtails. We walked along a forest track descending to a small waterfall. I chatted with Mr. Kikuta about the progress of conservation efforts of rare and endangered species. When I first met him in 2012, there were only around 700 Okinawa rails remaining, and there were real concerns that Okinawa’s most iconic species may become extinct. Since then, the Okinawa Prefectural Government has funded projects to protect the native species, including the eradication of the non-native mongoose, neutering and chipping domestic cats, and reducing roadkill. Eight years later, the latest estimates are around 2,000 Okinawa rails.

As we clambered over the thick roots of a giant sakishima suounoki tree (or looking-glass mangrove), we heard a distinctive kek-kek-kek-kek-kek birdcall. Mr. Kikuta pointed into the undergrowth, and I glimpsed the flash of an orange beak. There was the rustle of leaves, and then a pair of Okinawa rails peered out through the undergrowth. Before I had time to raise my camera, they had scampered back into the forest. I was not disappointed, as with renewed hope for the survival of the species, I know I’ll see them again on my next fantastic trip to Yanbaru.

Tips for visitors to Yanbaru

Slow down! It helps to take your time when visiting northern Okinawa. Locals request that you drive slow and carefully, to avoid hitting the local wildlife. If you see yellow warning signs for the Okinawa rail, be extra cautious. During May and June, the birds are raising chicks, and they are most likely to dash into the road.

Learn More

- Mangrove Kayaking (Yanbaru Ecofield Shimakazi) *only in Japanese

- Higashi-Village Tour Guide *only in Japanese

- KUNIGAMI VILLAGE Tourism Association

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Copy URL

Copy URL

Last updated 2021/12/20

Text by Chris Willson

Chris Willson is a British photographer, videographer, and travel writer based in Okinawa for over 20 years.